|

About the presenter: Stephen B. Hood, Ph.D., CCC-SLP, is a Professor and the former Department Chair and Clinic Director of the Department of Speech Pathology and Audiology at the University of South Alabama. His master's and doctoral degrees are from the University of Wisconsin. Steve is a Fellow of ASHA, a Member of the ASHA SID-4, and is a certified fluency specialist. The majority of his publications are in the area of stuttering, he has been active in the National Stuttering Association since 1978, and he was selected as the NSA Speech-Language Pathologist of the year for 2000. |

Desirable outcomes from Stuttering Therapy

by Stephen B. Hood

from Alabama, USA

In this article I will attempt to compare and contrast the two major, prevailing schools of thought regarding therapy for persons whose stuttering is a chronic, long-term, problem. I will also present ten statements that I believe are indicative of a successful treatment outcome. And finally, I will encourage you to harness your courage and use it to accept the challenges and the risks that are necessary for making meaningful changes in the way you talk. Helpful hints and strategies will also be given.

As adults who have stuttered for many years, I wonder if you have ever spent time trying to really understand the behavioral and emotional components that are involved with your talking and stuttering. I am sure you have experienced periods of "being stuck," but have you ever studied precisely what you do when you are "stuck?" I suspect that most of you have not. After all, going back to those moments of stuttering can be very unpleasant. Behaviorally, there are four ways to measure what you do to interfere with talking. One of these is the frequency with which you disrupt your fluency, and this is often measured in terms of the percent of words or syllables stuttered. The second component is effort: the struggle and physical tension associated with your stuttering. The third factor is the duration of stuttering, and involves how long a moment of stuttering lasts. Finally, you can study the types of things you do when you stutter: for example repeating sounds or syllable or words, prolonging sounds, or completely blocking on sounds silently. There may be some other things you do in an attempt to avoid stuttering such as pausing, substituting an easy word for a difficult word, paraphrasing what you want to say, or avoiding talking all together. Maybe there are some things you do trying to release or escape from the stuttering such as tapping your toe, or hitting your leg, or jerking your jaw. Emotionally, there are the feelings and attitudes that are on your stuttering plate. You may have negative feelings about speaking in general, and about stuttering in particular. Certain situations might be associated with more or less fear than others. There may be some changes in your mood. You might feel anxious, embarrassed, angry, and upset. Maybe you feel some guilt because of your stuttering, or maybe you are ashamed of the fact that you are a person who stutters. Your attitude is also important. Do you think of stuttering as being awful or terrible? Maybe you think stuttering makes you look insecure, or maybe you think that people perceive you as less intelligent because of your stuttering.

The concept of stuttering severity is highly complex because severity involves ALL of the behavioral and emotional components associated with it. Each person has his or her own equation for which are the most important, and I hope you will try to figure out what these are, for you.

Clinicians who approach treatment from a "Fluency Shaping" perspective strive to teach skills that will allow the person to speak fluently. The focus of treatment is on increasing the person's ability to maintain normal sounding conversational speech, and relatively little attention is focused on fear and avoidance. Success is measured through a reduction in the frequency of stuttered words and syllables. Fluency skills are learned first in the therapy room, and then transferred to situations outside of therapy.

Clinicians who approach treatment from a "Stuttering Modification" perspective are not concerned with shaping fluent speech, and are not primarily concerned with reducing the frequency of stuttered words and syllables. Rather, they seek to help the person reduce the severity of stuttering. They encourage openness, and acceptance of stuttering, they work to help desensitize the person to the behavioral and emotional aspects of stuttering, and instill coping strategies to help modify and manage the effort and struggle associated with stuttering. The person is helped to reduce the fear of stuttering, and reduce the avoidances that so often result from fear.

The speech targets of fluency shaping include such things as easy onsets, continuous phonation, breath support and light articulatory contacts. The targets of stuttering modification include such things as voluntary stuttering, pull-outs and preparatory. Although the goal of increased fluency via the route of fluency shaping may appear incompatible with the goal of stuttering modification to reduce the severity of stuttering, I think there are ways in which both sets of targets can be used together. Let me emphasize that I am not against the concepts of fluency shaping per se, but I have serious reservations about the way some people interpret them. Working to be fluent is certainly an acceptable goal, but several safeguards must first be recognized. Fluency is more than the absence of stuttering, so fluency should never be achieved by means of tricks, crutches, and avoidance tactics. Fluency shaping strategies that improve talking and enhance communication can pay dividends, but if they are misused in an effort to hide and conceal stuttering, then this will only serve to increase the underlying fear that triggers it.

There are many desirable outcomes that can result from successful treatment. I think the most positive outcome is one in which the person becomes an effective communicator:

- a person who can talk any time, any place, to anybody, ---

- a person who can communicate efficiently and effectively, ---

- a person who can do so with no more than a minimal amount of negative emotion.

The words "stuttering" and "fluency" are not included in this statement of outcomes. It is better to do more and more things to talk easily rather than more and more things in an attempt not to stutter. It is better to be open and honest about stuttering than it is to try to hide, conceal and cover up the stuttering. Desensitization can help reduce negative emotions, but not necessarily eliminate it completely.

Listed below are ten statements. How would your situation be different if you found that you could say "Yes" to each statement? How would things be if you reached the point where you agreed with all of these statements?

- I no longer need to chase the "fluency god."

- I can live without constant fear of stuttering.

- I can speak well without scanning ahead for difficult words.

- I can speak for myself, rather than rely on others.

- I can explore and follow career, social and leisure opportunities that require talking.

- I can make decisions in spite of stuttering, not because of it.

- I am not suffering or handicapped because of my stuttering.

- I don't feel guilty when I stutter, and I'm not ashamed of myself when I do sometimes stutter.

- I can communicate effectively, and feel comfortable doing so.

- I am really an "o-k person." I accept myself, and I like being me.

Therapy involves taking risks. But ask yourself these two questions: Do I see risk-taking as a challenge or as a threat?

Am I challenged to do better, or am I threatened by the prospect of doing worse? Hopefully, you will be challenged to face your fears and avoidances. Hopefully you will feel challenged to learn new and better ways to manage your talking. Hopefully, you will find challenges that motivate you to succeed. By accepting and acting upon the challenge to gradually increase your ability to cope with stress, you can gradually desensitize yourself to some of the fears, worries and uncertainties you have been experiencing. Desensitization does not mean that you necessarily like something; rather, desensitization helps you put up with it, cope with it, manage it, and not be at its mercy. By accepting the challenges and risks of making changes, you challenge and even threaten your comfort zone. Take the problem of avoidance as an example. What are some of the things you avoid? Maybe you have some feared sounds or words. Maybe you have some dreaded situations such as introducing yourself and saying your name, placing an order at the drive-up window, or making phone calls. Even though you know that substituting an easy word for a difficult word is not helpful in the long run, and even though you probably know that avoidance reduction is important, you also realize that the tasks and challenges you face are formidable.

It takes courage to accept the risk of reducing your avoidances. Here are a few examples of challenges and risks that you might accept.

- take a public speaking course

- join Toastmasters International

- place a call to a local radio talk show

- call a local hotel or motel and ask the clerk if you (say your name) have checked in yet

- participate in a public meeting by making a comment or asking a question

- read the "for sale" advertisements in the newspaper and then call to inquire about an item that someone is selling.

- call a local pet store and ask some questions about the care and feeding of the hamsters you plan to get for you're your spouse's birthday

- volunteer in a civic, church or social organization in a role that requires lots of talking.

Attempts to achieve spontaneous fluency, controlled fluency, controlled stuttering or whatever goals you have set for yourself will be difficult if not impossible to maintain if you are superimposing them on top of fear, anticipation, avoidance, shame and denial. Unless you have dealt with the negative attitudes and feelings, you are likely to make the mistake of trying to hide, conceal and interiorize your stuttering by making it temporarily covert.

I suspect that those of you who are still reading this paper are hungry for practical suggestions. I offer the following:

Many people who stutter strive for "speech naturalness" and want to be able to yak spontaneously rather than have to monitor their fluency and stuttering. The fact of the matter is that for most persons who stutter, particularly during the early stages of treatment, this is not possible. There are times of heightened communicative stress when they are more vulnerable and at risk for fluency breakdowns, and when vigilance and increased monitoring are required. Yes -- it is a pain in the neck to need to pay close attention to your speech, but often this is necessary. Maybe the following ideas will be helpful.

Get some post-it-notes and put them in locations where they will serve as helpful reminders. Stick them to the dashboard of your car, inside your notebook, or across your telephone. Come up with an abbreviated system of reminders:

- AVM -- Air - Voice - Movement (in your speech)

- KYMR -- Keep Your (Speech) Motor Running

- RTSE -- Remember To Start Easily

- NNTH -- No Need To Hurry

- RTSE -- Remember To Start Easily

Speech targets can help you manage your talking and modify your stuttering. Post-it notes can help you remember to monitor your speech in order to maintain air, voice and movement, and keep your speech motor running, etc. You might also want to purchase a small, spiral notebook that will fit into your pocket or purse so that you can keep a journal of your progress.

Whether driving a stick shift car or peddling a 10-speed bicycle, you need to remember that it takes more strength and energy to climb a hill than to coast on level ground. Much as you might like to cruise easily in overdrive, this is not always possible, and this is particularly the case when you are pulling a heavy load up the hill. Stuttering can sometimes be a heavy load, and communicative pressures and stresses can cause the road to be an up-hill climb. In anticipation of the approaching hill, you might need to down shift into a lower gear in order to manage the incline. You might need to gear down to a lower gear where you can monitor your talking and use your speech targets.

Whether you are working on techniques for fluency shaping, or techniques for stuttering modification, it is important to use them in the most positive way possible. Hence, it is more constructive to do more and more positive things to talk easily, rather than more and more negative things to not stutter.

Which of the following make sense to you?

- trying to get on base -- versus -- trying not to strike out

- trying to dive -- versus -- trying not to belly flop

- trying to ride a bike -- versus -- trying not to fall off

- trying to talk easily -- versus -- trying not to stutter

Indeed, the physical act of "trying not to stutter" (just like trying no to strike out, belly flop or fall off) is most likely to cause physical and emotional stress for you.

I'll bet you would like to have a dollar for every time some well meaning person has told you to "slow down and take your time," or to "slow down so that you don't stutter." I'll bet most of you have heard this many times, and that it still angers you when people give you this advice. One of the problems with this advice is that it is negative. It tells you to slow down so that something (stuttering) does not happen. This is confusing and makes no sense, the same way it is negative to try not to strike out, not to belly flop and not to fall off the bicycle. And to make matters worse, many people try to slow down by pausing in between words rather than slowing down by maintaining voicing and stretching out the syllables.

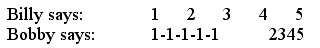

This is easier to explain verbally than in writing, but please bear with me. Which of the following persons is speaking more rapidly?

Billy and Bobby started at the same time, and finished at the same time, and so their actual speech rates are identical. Billy speech was smooth and easy. Bobby on the other hand stuttered quite severely on the first number, and then after escaping from the moment of stuttering, completed the last four numbers very rapidly. Bobby's speech rate was the same as Billy, but Bobby's articulation rate during the rapidly produced numbers from 2 through 5 was extremely fast. For many persons who stutter, their speech rates are slow because of the time spent stuttering; however, for many people, their articulation rates during rapidly produced, short bursts of fluent words, is extremely fast.

By slowing down the articulation rate by maintaining voicing and "stretching out the syllables" you might find that your speech rate is actually increasing, because you are not spending so much time stuttering.

Billy: "Mmyy nnaame iiz Biilly."

Bobby: "My name is B-b- bbbbbbbb ah, um, buh-buh-buh um mynameisBobby."

Earlier in this paper I referred to the fact that one of the major behavioral features of stuttering involves duration: how long does stuttering take? To what extent does it slow you down? Many persons who stutter worry greatly about time-pressure. Consequently they try to say things rapidly and are in a great hurry to begin and then end what they are saying. During moments of stuttering they are in a major rush to escape the moment of stuttering and they hurry and try to talk rapidly before they stutter again. They get upset when they have a lot to say, and have only a short time to say it. These are examples of time pressure. The "NNTH" acronym mentioned earlier is an attempt to help with this (No Need To Hurry.) Rather than rushing to escape from moments of stuttering, it might be helpful for you to try to "remain in the stuttering moment" in order to allow you to release from it in a manner that is slightly slow, deliberate, gradual and voiced. Clinicians sometimes work to help people "freeze and release" and employ "gradual pullouts" to help regain and then maintain ongoingness in speaking; however, these targets do now work well if you are in a battle for escaping from stuttering moments in ways that are quick, abrupt and tense.

Think about the language you use when you talk to yourself about your stuttering. What do you say to yourself? If you are like most people, you tend to label things rather than describe them in behavioral terms. Consider the following questions and answers:

Q: What happened? A: I got stuck

Q: What happened? A: I had a block

Q: What happened? A: The word wouldn't come out

Q: What happened? A: I had trouble with that one

In more than 35 years of clinical work I have never seen a word get stuck in somebody's throat. The answers in the right-hand column attempt to label an event as "happening" rather than to describe the behavior events that the person did. It is almost like there is a puppet on a string, and things are being manipulated so that things happen to the puppet. But when it comes to you and your speech, it is important to use the language of self responsibility, and to describe what you are doing. Now, please consider these examples:

Q: What were you doing? A: I was tensing my jaw

Q: What were you doing? A: I substituted an easy word for a hard one

Q: What were you doing? A: I was saying "um-um-ah," to stall for time before saying the next word

Q: What were you doing? A: I repeated the first syllable three times>br?

By being more descriptive of what you are doing, you are accepting more responsibility for having done it. You are DOING something, rather then thinking in terms of what HAPPENED to you. And if you think of what you are doing, then you can also think of what you can do to change and modify it.

Attempts to hide, conceal and cover up stuttering contribute to the overall severity of the problem and make it worse than it needs to be. Stop beating yourself up!!! Try to accept your stuttering, and be willing to acknowledge it in socially acceptable ways. This is not to say you should seek "sympathy" for stuttering -- but rather, to show your listeners, as well as yourself, that stuttering is "ok."

One way to show acceptance and tolerance for stuttering is by being willing to stutter voluntarily, on non-feared words. You probably do not want to do this, and probably rationalize not wanting to do this by saying such things as "Well, why do this? -- my listener already knows that I stutter." This may be true, but your listener may not know that you can be cool about stuttering, that you can accept some stuttering, and that you can be open about it. In addition to admitting stuttering to your listeners, you are also admitting stuttering to yourself.

You can show acceptance of stuttering in ways that do not directly involve speaking. There are inexpensive things you can purchase from the National Stuttering Association that will allow you to show acceptance: e.g., coffee mugs that say ŚNational Stuttering Association.' Both the National Stuttering Association and the Stuttering Foundation of America sell posters of famous people who stutter. In my office I have a framed picture on the wall, and coffee mug on my desk. Things like these might look good in your home or office.

If people tease or kid you about your stuttering, learn to handle it in a socially acceptable way. For example, if someone is giving you a hard time about stuttering you might say something along the lines of the following:

- If someone asks you if you have any hobbies and interests, you can answer by saying: "One of my hobbies is stuttering. I've been practicing, and am getting really good at it."

- If someone asks you if you have stuttered all your life, answer by saying: "Not Yet."

- If someone comments on your stuttering, you might say

"Sure I stutter. What are you good at?"

"Sure I stutter. Do you want me to teach you how to do it?"

"Stuttering is OK, and I have permission to do it."

The National Stuttering Association has t-shirts that have the NSA Name and logo on the front. I developed something for the back of the t-shirts that people can wear to help advertise their stuttering: "Stuttering is OK -- Because What I Say Is Worth Repeating." In recent years these have been auctioned as a fund-raiser at the NSA banquet.

Persons who stutter are among the most courageous people I know. For some of them, every word in every sentence of every conversation presents challenges and potential obstacles that must be faced. At times, the challenges may seem almost unbearable, and yet these people persist and move onward and upward. Maybe these people are mindful of the words of New York Mayor Rudy Giuliani, who in reference to the horrors of September 11 said, "Courage is about the management of fear, not the absence of fear." My hope for you is that you accept the challenge to do more and more things to talk easily and communicate effectively, rather than be threatened by the prospect of severe stuttering. Best wishes for developing the courage to take the risks that will lead you forward on a successful and satisfying journey.

August 19, 2003