|

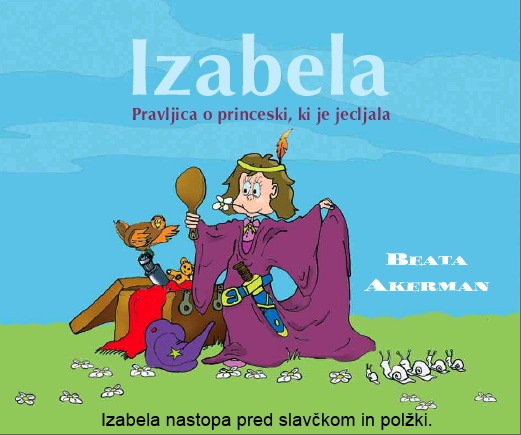

About the presenter: Beata Akerman is a young researcher in the Faculty of Social Work, University of Ljubljana, Slovenija, a social worker specializing in social work for people with special needs, and is planning a doctoral dissertation about educational and employment opportunities for people who stutter. She is a person who stutters and because stuttering in Slovenia carries a big stigma, became an activist, fighting for the rights of people who stutter. She has written many articles, participated in television and radio shows, conferences, and has published a children's book about princess Izabela who stuttered for which she won a special award in Austria for the best international children and young people's literature. |

My stuttering is no longer holding me back

by Beata Akerman

from Slovenia

I started to stutter when I was 4 years old. About a half year before I actually started to stutter, I became very hoarse for several months. Doctors could not discover any reason why this happened. When my voice returned, I started to speak very quickly. A short time later, I started to stutter. At first my stutter was quite mild. Preschool speech therapy treatment did not help.

Everything changed when I started primary school where other children and unfortunately some of the teachers made fun of me. I started to stutter much more severely and it stayed that way until now. I was afraid to open my mouth and speak, because I knew that everyone would laugh at me. With no friends and low self-confidence, I made it through the primary school. Those years were the hardest years of my life, but those experiences made me who I am today. I learned how to fight for myself and not allow other people to judge me based on my speech.

Growing up with a stutter and not having anyone to talk with about problems related to stuttering was very difficult. No one can understand those problems better than someone who actually stutters. I was ashamed of myself, always wondering "Why me?" Other children made fun of me and nobody really understood what I was going through. I never showed them how much they hurt me. I promised myself that someday I would become activist and fight for the rights of those who stutter. I didn't want anyone to go through the same experiences alone like I did.

If a person is blind or uses wheelchair, you can see that pretty quickly. But with stuttering, it only becomes obvious when one starts to talk. At that point, the listener's behavior often changes. Because the awareness of Slovenian society about stuttering is negligible, there are many people who believe that people who stutter are shy, not very clever, lazy, nervous, unsociable, and especially that the stutterer is very strange. Once, a colleague of mine, who didn't know me that well, asked me, if I stutter. When I said yes, he smiled at me and said: But otherwise you look so normal! My friend has a brother who stutters severely. When he brought home a new girlfriend to meet his family she said, "You never told me you have a retarded brother!" Some people still believe that stuttering is a disease. When I was a student of social work, I worked for a year as a volunteer in the Youth center. There was a small girl. Her parents soon prohibited any contact with me, because, as I was told later, they believed, that there was something wrong with me and if their daughter will keep on seeing me, she'll start to stutter! It is also common that a PWS is perceived as having a drinking problem or is a psychiatric patient.

In Solvenia, appearance is very important. Being "beautiful" means two very different things for women and men. I'm reminded of Bob Dylan's song "Ugliest girl in the world". The title alone speaks for itself, but the lyrics of the song are even more offensive toward women who stutter. The song is about a girl, who is supposed to be the ugliest girl alive.

Her eyebrows meet, she wears second hand clothes

She speaks with a stutter. . . .

The woman that I love she got two flat feet

Her knees know together walkin' down the street

She cracks her knuckles and she snores in bed

She ain't much to look at. . . .

So it seems, being a beautiful woman includes NOT STUTTERING!

The everyday experience of a person who stutters in Slovenia is that many people make fun of us. They laugh at us, speak to us as if we were small children or that there is something wrong with our intelligence (speaking loudly and slowly, using short sentences as if we were incapable of understanding what they were saying). Some don't even listen to us. Others are full of advice on how to talk and breathe so we won't stutter. Others pity us.

For many years I never talked about my stuttering or about being teased. I didn't want to upset my mother who was always very supportive and told me that it is not important how I talk, but what I say.

When I was 22, after a third unsuccessful experience with speech therapy, I became aware that I needed to accept myself for who I am. I am a person who stutters and there is nothing wrong with that. When I reached that point in my life, my stutter was no longer a problem for me. It is said, that if you cry because the sun has disappeared from the sky, the tears will prevent you from seeing the beauty of the stars! I will never talk without stuttering but I can still achieve so many things in my life. There is nothing wrong with being a person who stutters, but in my opinion it is very wrong if one tries to deny it. Today I am no longer ashamed of myself because I stutter. My stutter makes me unique and I'm a stronger person because of the fact that I have had this experience. I'm no longer trying to be someone who I'm not. It is a relief to finally feel good about myself, not being afraid to speak up and stand up for myself and others. So what if I stutter?

In 2006, at the age of 24, I wrote a thesis entitled 'Living with Speech Impediments Through the Eyes of People who Stutter' exploring different aspects of the lives of people who stutter, difficulties that lie within each individual and ways in which these problems influence the individual's self image, their own speech and their daily life. I also finished postgraduate studies in social work for people with special needs where my main area of interest was representation of people who stutter in the media, writing a specialist thesis 'Changing public discourse about people who stammer in Slovenia'.

In my research about how stuttering is depicted in the books and movies, it became clear that often the character who stutters embodies every negative stereotype about stuttering - they are shy and not very bright, or even worse, they are murderers, rapists, prisoners, or emotionally disturbed.

I decided to write a children's story choosing a character that embodies grace, goodness, wisdom and beauty, with the intention to break the stereotypical image of PWS and thereby helping to reduce problems that especially children who stutter face. The story is about a princess named Izabela who is, at least in Slovenijan children's literature, a very unique character because she stutters. Some parts of the story are taken from my life. The fairy tale helps readers accept stuttering, not as a deficiency but as simply something that makes the individual unique.

The above presentation is an adaptation of an interview by Dr. Sachin Srivastava from India. It is included as a paper for this online conference with permission.

SUBMITTED: March 13, 2011

Return to original language with "show original" button at top left.